In April, ConnCAN released its Early Childhood Report, “Lessons from the Field.” The report highlighted early childhood providers with proven track records of success from across the country. We asked each of the providers to pen blog posts for us on various topics. The following post was written by Christie Huck, Executive Director of City Garden Montessori School in St. Louis, Mo.

When educators and researchers talk about early childhood education, something that has become known as the “word gap” often becomes a primary focus. In 1995, researchers Betty Hart and Todd Risley embarked on a study over four years to determine language differences between low-income families and more affluent families. The researchers found that, by age three, children with high-income families were exposed to 30 million more words than children with families on welfare.

This study, though it was widely critiqued for its methodology, has become recognized as a primary source of information regarding academic achievement gaps between low-income children and more affluent children. The study has inspired many initiatives to improve the academic performance of low-income children, with a focus on eliminating the “word gap.”

In her 2015 articles in both The Conversation and New Republic, researcher Molly McManus debunks the notion of this “word gap”:

Unfortunately, the focus on the “word gap” takes teachers and other educators away from thinking about how to address the larger issue of inequality in education. Instead, it focuses attention on what children do not have in terms of an arbitrary word count.

Moreover, when we use the “word gap” to identify poor children as behind before they even begin school, that affects their teachers’ view of what they are capable of doing. It directs attention toward the things that poor families do not have and cannot offer their young children.

McManus goes on to say that educational disparities are a result of different educational experiences that low-income and more affluent children are afforded at school, and that our focus must shift from the “word gap” toward the “opportunity gap.”

At City Garden Montessori School in St. Louis, Missouri, eliminating opportunity gaps has become our primary focus. The academic disparities that exist across the United States also exist within our school–and we recognize that these disparities have significant lifelong impacts for our students. We have challenged ourselves to deeply examine what we are doing and how we are serving our students, to determine factors that are contributing to opportunity gaps. We know that how we serve our youngest students is especially critical to eliminating life-long opportunity gaps.

It has become our goal to design a school that is meant to educate everyone. We are reimagining school in a way that prioritizes inclusive excellence, academic rigor for all students, racial equity, and connection through community.

This begins, most importantly, with our youngest students.

In her book Can We Talk About Race? And Other Conversations in an Era of School Resegregation, Beverly Tatum states: “American schools were never designed to educate everyone” (2008). Our schools are the product of a society, Tatum says, that was very intentionally designed to benefit some and to keep others from succeeding. At City Garden, we have had to examine how this reality has surfaced in our school and what we must do to interrupt patterns and structures that keep all children from thriving.

It has become our goal to design a school that is meant to educate everyone. We are reimagining school in a way that prioritizes inclusive excellence, academic rigor for all students, racial equity, and connection through community.

This begins, most importantly, with our youngest students.

The Montessori Theory of Development offers what we believe is an ideal framework to accomplish this work. Maria Montessori described the way the young child interacts with his or her environment as “the absorbent mind”—the sponge-like capacity to absorb from the environment what is necessary to develop into a full, thriving human being. What the child takes in during the absorbent mind period is taken in effortlessly and remains as the foundation of his or her personality.

During the period from birth to age six, children’s identity is developed, in relation to the culture in which they live. The foundations that are established during this period set the stage for the child’s future cognitive, physical, emotional and social development. The child’s self-concept is formed, as well as their understanding of who they are in the world and what their role is in society. As the child develops and matures after age six, information is taken in through conscious work and memory, or the “reasoning mind,” and, though this later period is also important, information taken in at later stages is not as foundational to the personality.

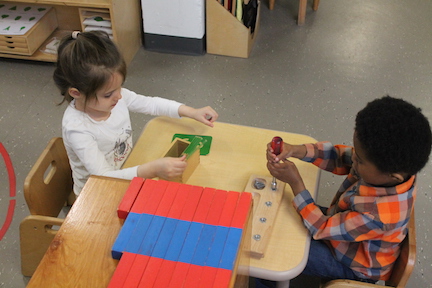

The Montessori early childhood classroom is designed in keeping with the power of the absorbent mind. Children are introduced to language, math, geography, cultural studies, the sciences, art, music, and many practical life activities. Children are deeply respected and are allowed significant autonomy and choice. They absorb everything around them effortlessly and are empowered to become as independent as possible at a very young age.

We must keep in mind, however, that while the absorbent mind provides educators an enormous gift, it also offers us a tremendous responsibility. As stated, at this early stage, the foundation of a child’s self-concept is formed. If the environment does not acknowledge or celebrate the child’s gifts and strengths, or offer a diverse selection of experiences, the window of the absorbent mind may begin to close before the child is able to effortlessly take in information that will help them thrive and develop into their full potential. This has much less to do with the number of words a child hears or sees, and much more to do with having teachers and staff who are culturally competent, having a wide array of stimulating activities available to every child, and having a physical and emotional environment that is empowering and supportive of every child and his or her family.

In short, if a child’s early childhood experience does not deeply and holistically meet their needs, we are missing a very important opportunity to set them up for lifelong success.

Preparing child-centered, equity-focused educational environments for our children from birth to age six is perhaps the most important thing we can do to eliminate opportunity gaps and to create transformational change–true equity–in the United States.

Imagine what could happen if every child’s full potential were unleashed, and if every child were given the full opportunity to become who he or she is meant to be. Imagine the society we could become.

Imagine.